User Accessibility Testing: Going Beyond Standards

There is something about web standards that seems antithetical to web accessibility work. Our goal is to make our websites usable to the varied kaleidoscope of human ability and preference, and whenever you start drawing borders on what is and isn’t acceptable, something is left on the outside.

I don’t mean to say standards aren’t good and necessary. There are a lot of baseline things that our field needs to continue doing to make the web better, and standards, especially internationally accepted ones, like the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG), help people get there.

But when we adhere to standards alone, we are ultimately excluding people.

Enter user accessibility testing

Lately, at Capellic, we’ve been partnering with Knowbility’s AccessWorks program to test the websites we build with people with disabilities. And I find the vast majority of issues that come up during these tests fall outside of WCAG.

Maybe it's because our sites already hit the basics. Before we run usability tests, we test our sites ourselves against standards like WCAG. We run each page template through three different automated accessibility analyzers (WAVE, Sa11y, and Axe Devtools) and conduct a series of manual tests, including keyboard, reflow, and screen reader testing.

But each time I conduct a user accessibility test, I find a host of accessibility-related issues that fall outside of WCAG standards.

Here are a few issues I’ve observed in recent tests.

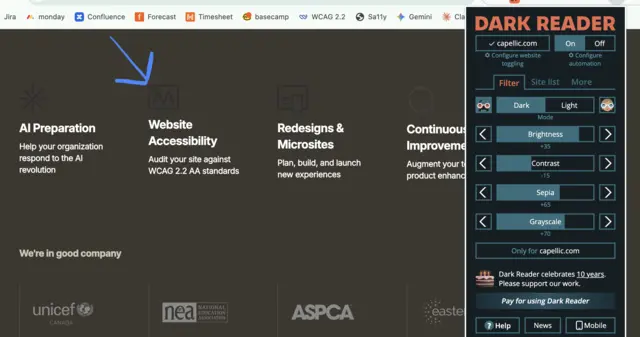

- I’ve had multiple test participants with low vision use a Chrome extension called Dark Reader that allowed them to view a site in dark mode and apply other color alterations. Even though the sites we tested didn’t offer an official “dark mode” or “high-contrast version”, I realized we could do more to make our sites work better with tools like Dark Reader. Like applying text colors to wrapping HTML elements and using the CSS CurrentColor variable for text and SVG icons.

- A few of the test participants used screen readers to access the web. The participants all slowed down the screen reader’s output so I could follow along. We found a number of issues in our code that added unnecessary verbosity to the screen reader’s output, slowing down their experience. For example, semantic markup (like overuse of the <article> or <section> tags) resulted in screen readers announcing “article” or “section” out loud, which didn’t provide any important context in our particular use case.

- A few test participants used screen magnification, and one zoomed in 400% in the browser while their screen was already quite small. I usually follow WCAG’s Success Criterion 1.4.10 Reflow, which says you only need to support designs down to 320px wide at the smallest, but in testing with real users with low vision, I found we need to support experiences smaller than that. When these participants zoomed in on already small screens, everything was crammed together, and many links went offscreen, making them impossible to select.

- A few test participants who navigate the web using only their keyboard (due to mobility-related disabilities) used the arrow keys much more frequently than I did during my own keyboard testing. I tend to rely on the tab key. So I’ve started ensuring that both the tab key and the arrow keys can be used to navigate features like dropdowns.

So what exactly is user accessibility testing?

User accessibility testing is when you run a usability test with people with disabilities and folks who regularly use assistive technology (AT) to access the web (like screen readers, screen magnifiers, and alternative keyboards).

The goal with this kind of testing is to unearth any issues with a site’s content, design, or code that present barriers to individuals with disabilities.

For most of the tests we’ve done for clients at Capellic, we partner with Knowability’s AccessWorks program to recruit participants and conduct five one-on-one, remote tests. Each test lasts around 45 minutes to an hour.

During the sessions, the moderator (usually me) will ask participants to share their screen while they attempt to complete 4-5 tasks on the website, and narrate their thoughts as they go.

For website redesigns, we try to run these tests as close to launch as possible, since that's when the website, including the content, is finalized. We want the tests to reflect the real experience someone will have on our site. And we save hours to remediate any critical issues that may come from the testing.

Test Participants

There are different programs that recruit people with disabilities to participate in usability studies, such as Fable, Knowbility, and WeCo. We did a review of a few different organizations about a year and a half ago and landed on Knowbility as the best program for our needs.

We found Knowbility's twofold mission compelling: to help make websites and applications more accessible for everyone, and to provide supplemental income to individuals with disabilities.

Knowbility’s database of test participants is categorized by disability and preferred assistive technology. You can request participants, for example, with hearing-related disabilities, if you know your site has a lot of multimedia content. You can also request participants who use different screen readers (for example, one participant could use JAWS while another uses NVDA).

To keep timelines and budgets down, we tend to limit each test to 5 participants. Once testing is complete, we suggest to clients where it may be useful to conduct additional testing in the future.

Open-ended questions

During each test, I usually reserve the first 10 minutes for a few introductory questions like:

- Could you please introduce yourself, what disabilities you have, and how they affect your experience navigating the web?

- Do you typically browse the web on a laptop or on your phone? Or another kind of device? Do you use different assistive technology depending on the device?

These questions help to get an understanding of the test participants' background and experience. There is a big difference between an expert lifelong screen reader user and someone new to using one.

I also like to ask a few other questions related to our clients’ (or my own) interests in the web accessibility space. Questions like:

- Do you ever use accessibility overlays or widgets when they appear on a website? Tools like AccessiBe or UserWay that let you change font sizes or colors? Why/why not? [EVERYONE, I mean EVERYONE, has said “no” to this question. Many participants emphatically hate these types of tools.]

- What is your opinion on AI and how it might change your experience navigating the web with a disability? [Surprisingly to me, given the backlash against craptions, almost everyone I ask this question to has a positive outlook on AI.]

Scenario-based task-flows

Before I facilitate any type of usability study, I create a research plan and a moderator’s guide with 4-5 scenarios to use during the test.

These scenarios are always anchored in the website’s goals and expected audience needs and journeys. Here are a few scenario-based tasks from some of our recent tests:

- Can you show me how you would look for a resource that provides autism screening for children on this website?

- Imagine that you are looking for legal assistance related to a case of domestic violence for someone in your family. Starting from the homepage, show me how you would use this site to find the contact information for an organization near you that could help you with legal assistance related to domestic violence.

- Imagine you found this article helpful. How would you find similar articles on this website?

I ask each participant to “think out loud” while they are trying to accomplish each task and specifically call out anything they find frustrating (accessibility or usability related).

Sometimes, participants do things I don’t expect. Recently, when one participant couldn't find what I asked them to find, they opened an AI window and asked the AI to complete the task. I’ll get responses like, “Honestly, I’d Google it,” instead of trying to find something on the site using the on-site search.

While these detours to search engines and AI won’t reveal any accessibility bugs, it’s always interesting when they pop up.

How does user accessibility testing relate to other types of user research and testing?

User accessibility testing is just one activity of many that we like to do with our clients to ensure the sites we build are as accessible and user-friendly as possible.

It is important to remember that the participants in this test typically won’t fall into your direct audience. User accessibility testing shouldn't replace user research activities that involve listening to the people you are trying to reach.

It also shouldn’t replace performing a standards-based accessibility-focused quality assurance phase performed by an expert in web accessibility (like someone certified by the International Association of Accessibility Professionals). The user accessibility tests will never include enough participants to cover every possible disability and preference. We rely on standards to cover that baseline level of accessibility—and as a bonus, improve a site's SEO value.

Hasn’t AI fixed web accessibility already?

No. It hasn’t.

I’ve found it hard to take on any accessibility project these days without confronting some form of “will AI make this irrelevant?” question. Some people think AI will solve everything. Not only is an “AI-solves-everything” future far from promised, it’s simply not here right now.

We need to remain vigilant and do the good work to design and build accessible experiences.

Your users want and deserve access to your content now. Do not wait for some hypothetical future where robots have fixed all of our problems.

What does it take to start running user accessibility tests?

If you want to run user accessibility tests on your site at your organization, here are the steps we take to get started:

- Get buy-in (and budget) from your organization’s leadership. Highlight how real-life testing is the best way to go beyond the inherent limitations of standards.

- Write a research plan and moderator’s guide. Write 4-5 scenario-based tasks to run during the tests that are anchored in your site’s goals and audiences.

- Reach out to Knowbility or Fable to help determine participants and timing.

Once you finish running your tests and are evaluating the responses, remember that accessibility is not a monolith. These are individuals giving you their individual feedback, and you may hear a request for a change to your site that might:

- Help this one particular person, but hinder someone else’s access to your site

- Go against WCAG standards

- Hurt the broader usability of your site

- Be better accomplished through a different type of change

Have someone experienced in web accessibility and usability evaluate the results of the test and determine how best to move forward.

Remember to share your findings with your organization's leadership to show the value of your work.

(And, of course, we’re here if you don’t want to handle it in-house. You can get in touch below.)

Good luck testing!